Viewing and Treating Pelvic Floor Dysfunction with a Global Lens – by Julie Hammond

Image by Anna Satmari –

A few days ago, while standing in a long queue for the checkout in my local supermarket, I noticed so many different packs of adult liners on offer for incontinence problems for men and women. Clearly there is a lot of demand. When did this become ok? In Australia, 10% of men and 38% of women suffer from urinary incontinence (Continence Foundation of Australia, 2019). The Continence Foundation of Australia also found that 62% of people suffering do not seek treatment. Why? What is stopping people from talking about this and seeking treatment? Often there is shame, embarrassment and maybe the feeling, especially after childbirth or menopause, that it is just something we must live with. This is not true and shouldn’t just be accepted as normal; however, finding treatment can be a minefield. Wouldn’t it be nice as health professionals if we could make it easier for clients to know who to see? Wouldn’t it also be nice if this was a subject that was easier for men and women to talk about?

Treating pelvic floor dysfunction, or as I am going to call it for the rest of the article, pelvic diaphragm dysfunction, should be a multidisciplinary approach with collaboration between health professionals. It involves exercise (but not just strengthening exercises), awareness, proprioception, interoception, relaxation. There is always an emotional component that goes with pelvic diaphragm dysfunction which also needs to be addressed. The most common form of incontinence is stress urinary incontinence, which is involuntary loss of urine due to increased pressure from coughing, sneezing or exercise (Nie et al., 2017). Urge incontinence is the sudden urge to urinate with an involuntary loss of urine. Pelvic diaphragm dysfunction is often attributed to weakness of the pelvic diaphragm, but this isn’t always the case. There can be weakness or underactivity, there can also be muscle tightness and spasm and overactivity, or it could be due to pelvic dyssynergia where the muscles in the pelvic diaphragm lose coordination (Scott et al., 2019).

Local Lens/Zooming In

Understanding the fine detail

In this article I explain the fine detail before looking at the bigger picture, but in clinical practice this isn’t the treatment protocol. Looking at the fine detail is important but then zooming out and looking at the bigger picture is needed before you plan your strategy. Making sure the pelvis has enough support from above and below before easing tension in the pelvic diaphragm is important, otherwise the client may not be able to cope with or hold the changes.

The Pelvis

The pelvis is made up of the two innominate bones or Os coxae, the sacrum and the coccyx. Each of these innominate bones is made up of three fused bones, the ilium, the ischium and pubis. In standing and walking the pelvis functions to transfer load of the upper body onto the lower limbs. It protects the pelvic organs and allows for childbirth and provides attachments for muscles, ligaments and fascia.

The pelvic diaphragm

The pelvic diaphragm anatomy can at first appear overwhelming, made up of interrelated structures of muscles, ligaments and fascia. According to Stoker (2009) the pelvic diaphragm consists of four layers; the endopelvic fascia, the muscular pelvic diaphragm, perineal membrane and superficial perineal layer. The pelvic diaphragm functions to maintain continence, facilitating bladder and bowel movement, whilst giving support to the pelvic organs, helping to stabilise the hips and Si joint from within, important in sexual function and forms part of the birth canal (Stoker, 2009; Bordoni et al, 2020)

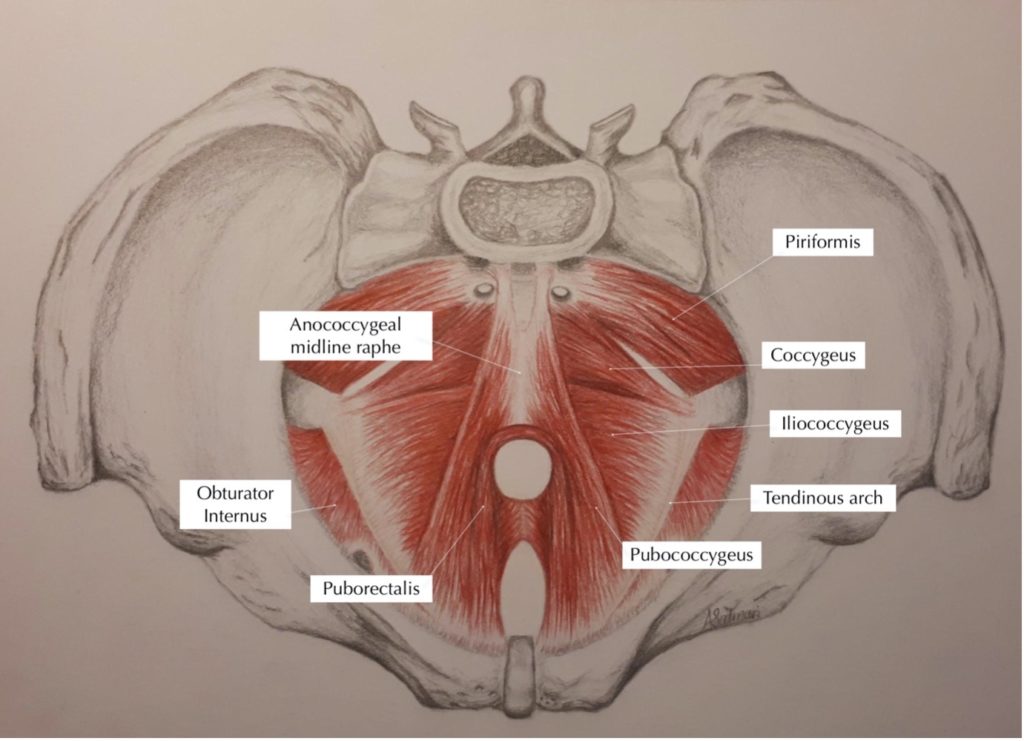

The pelvic diaphragm muscles (PDMs)– refer to figure 1

The muscular pelvic diaphragm is made up of the levator ani musculature and coccygeus. The levator ani consists of the iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus and pubovisceralis more commonly known as puborectalis, which can also be subdivided depending on its attachments to the urethra, vagina and anus. We also have piriformis forming part of the back wall and obturator internus.

Iliococcygeus: arises from the posterior half of the tendinous arch of the levator ani and the ischial spine, inserting into the coccyx and midline anococcygeal raphe (iliococcygeus from both sides interdigitates to form the midline anococcygeal raphe, along with the posterior fibres of pubococcygeus). This median raphe is also known as the levator plate between the anus and coccyx and supports the pelvic organs (Herschorn, 2004).

*Tendinous arch/ tendinous arc/ arcus tendinous (changes depending on the literature) of levator ani runs from the pubic ramus to the ischial spine and it is a thickening of the connective tissue that covers obturator internus

Pubococcygeus: Is the more medial portion of the levator ani, it arises from the anterior half of the tendinous arch and the posterior surface of the pubic bone, inserting into the anococcygeal raphe and coccyx (Stoker, 2009).

Puborectalis: Is a sling like muscle originating laterally from the pubic symphysis on both sides and encircling the rectum. Contraction of the puborectalis creates an anorectal angle; this angle and puborectalis assist in preventing defecation. Puborectalis has resting tone and can also contract rapidly to prevent incontinence with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. The urogenital hiatus is a gap anterior of the pelvic diaphragm that the urethra and vagina pass through; contraction of puborectalis leads to narrowing of the urogenital hiatus.

Figure 1. The muscular pelvic diaphragm

Image by Anna Satmari

Global Lens/Zooming Out

Looking at the bigger picture

Pelvic diaphragm and respiratory diaphragm connection:

The pelvic and respiratory diaphragm are structurally and functionally intimately linked. The respiratory diaphragm is the principal muscle of breathing as well as providing trunk stability along with the abdominals (often bracing and providing too much stability but that is a topic for another article). The pelvic diaphragm muscles and the respiratory diaphragm work with the abdominals to react and control changes in intra-abdominal pressure (Park & Han, 2015). During inspiration as the respiratory diaphragm moves downwards the pelvic diaphragm relaxes, being aware that it doesn’t fully relax it just eases tension, to assist in increasing inspiration. During exhalation or coughing or sneezing they contract (not always for some of us), increasing intra-abdominal pressure and assisting the diaphragm to move upward. Park & Han (2015) found that with contraction of the pelvic diaphragm muscles, the motion of the diaphragm was hindered. Hypertonic pelvic diaphragm muscles are a common problem in clinical practice and clients get frustrated that they can’t strengthen their PDM, but they are already working too hard and need relaxation techniques first. This has a knock-on effect on breath and breathing dysfunction and can in turn have a knock-on effect on pelvic diaphragm function, along with anxiety (Paulus, 2013) and so the circle continues.

Compression from above:

I have been fascinated in clinical practice with compression from above; it can be abdominals, obliques, upper chest and shoulders that contribute to a look of shortening and heaviness in the upper body. Compression from above increases intra-abdominal pressure, affecting the pelvic diaphragm and in particular the pelvic organs and the breath. I have found in clinical practice, women with prolapse or urinary incontinence can often have a pattern of compression from above and, as part of the treatment strategy, easing and lifting tension in the abdominals not only helps with breath dysfunction but is also important for pelvic diaphragm function. Also easing shoulder tension and compression, will have similar benefits for some clients. I was very excited when I read a blog by Diane Lee about chest grippers (what I term compression from above). In this blog she describes a postural pattern of upper chest and abdominal tension which causes the lower abdominals to protrude, due to an increase in abdominal pressure. She states that symptoms of this pattern lead to disordered breathing patterns, an increase in intra-abdominal pressure putting pelvic organs at risk of prolapse or stress urinary incontinence.

Pelvic diaphragm and foot connection:

My other interest in clinical practice is the connection between lower leg position, foot position, adaptability of the feet and PDM function. Studies have shown that the pelvic angle is changed by the ankle position (Chen et al., 2009; Kannan et al., 2017; Lee, 2019) and therefore, can alter the contraction of the PDMs. However, the research had contradicting results. A study by Chen et al. (2005) looked at how the ankle’s position could change the PDM contraction strength. The study included 39 women, all with SUI. PDM activity was measured in standing in three different ankle positions, neutral, plantarflexion (PF) and dorsiflexion (DF). When the ankle was in PF, the pelvis posteriorly tilted, and in DF, the pelvis anteriorly tilted. The results showed that PFM activity was weakest in PF and most significant in ankle DF. This study had its limitations as the ankle movement was passive and didn’t consider active movement on PDM activity. A similar study that used active and passive ankle positions (Chen et al., 2009) tested PDM activity in nine different ankle positions, with horizontal as a baseline. They tested active DF at two different heights, passive DF and PF, and PF and DF with arms raised. Results showed that PDM activity was more significant in all ankle positions than horizontal but no significant difference between PF and DF. The greatest significant difference was the mean maximum contraction of the PDMs in PF with the arms raised, closely followed by passive DF with a 4.5cm block. Ankle neutral had the weakest PDM activation. The results show that ankle position can change PDM activation but are contradictory on which position is optimum.

A newer study by Lee (2018) also looked at ankle position and its effect on PDMs but with active movement. The participants in this study were 24 men and 26 women with no history of SUI (it would have been good to see this study on people with history of SUI). As well as measuring PDM activation, electrodes measured muscle activity and tracked body segments. The data was collected in ankle neutral, DF and PF. The mean measurement showed PDM activity was greatest in DF, then PF and weakest at neutral. The motion analysis showed that in DF, the pelvis tilted anteriorly and increased the activation of the PDMs. It didn’t show change in pelvic position in PF, which was different from the study by Chen et al. (2005). The research is contradictory but does show changes in pelvic diaphragm muscle activation with the feet in different positions. It also shows that each person’s pelvic dysfunction is unique and treatment strategies and exercise need to be tailored to suit the uniqueness of each individual.

Clinical relevance:

I love listening to Carla Stecco lecturing and after she has given you a lot of information she always asks, “what means?” This one question sits with me whenever I am preparing a lesson or writing. You can get lost in the information but what does it actually mean? In clinical practice, treating women with pelvic diaphragm dysfunction or pain is a multidisciplinary approach. Pelvic diaphragm dysfunction is more than just a pelvis problem and many factors need to be looked at. I am a great believer in collaboration and working with other health professionals for the good of the client. Internal work for the pelvis has its place but in what sequence of the treatment? Making sure the client has a good foundation and support and can then cope with the changes that need to be made. A local understanding of the problem, followed by a global assessment and treatment, before going locally to treat the pelvis. What if you ease the pelvic diaphragm but the client has compression from above, how will this impact the pelvic diaphragm and can the person maintain the change, no! Do they have support from underneath, what position is the lower leg in? Are they already starting the exercise in plantar flexion or dorsiflexion of the lower leg? What position is the pelvis in? How will this impact the pelvic diaphragm balanced within the bony pelvis? These are all questions that need to be looked at before exercises are given. Then thinking how can I help ease and balance the pelvis/ lower leg/ foot that will help the exercises be more effective?

References

Continence foundation of Australia (2019). Continence in Australia, a snapshot.

Chen, C., Huang, M., Chen, T., Weng, M., Lee, C., & Wang, G. (2005).

Relationship between ankle position and pelvic floor muscle activity in female stress urinary incontinence.

Urology (Ridgewood, N.J.) 66(2), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2005.03.034

Chen, H., Lin, Y., Chien, W., Huang, W., Lin, H., & Chen, P. (2009). The effect of ankle position on

pelvic floor muscle contraction activity in women. The Journal of Urology, 181(3), 1217–1223.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.151

Herschorn, S. (2004). Female pelvic floor anatomy: the pelvic floor, supporting structures, and pelvic organs.

Reviews in Urology, 6 Suppl 5 (Suppl 5), S2–S10.

Kannan, P., Winser, S., Goonetilleke, R., & Cheing, G. (2019). Ankle positions potentially facilitating greater maximal contraction of pelvic floor muscles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(21), 2483–2491.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1468934

Lee K. (2018). Activation of pelvic floor muscle during ankle posture change based on a three-dimensional

motion analysis system. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and

Clinical Research, 24, 7223–7230. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.912689

Lee K. (2019). Investigation of Electromyographic activity of pelvic floor muscles in different body positions to

prevent urinary incontinence. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental

and Clinical Research, 25, 9357–9363. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.920819

Nie, X., Ouyang, Y., Wang, L., & Redding, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of pelvic floor muscle training

for the treatment of urinary incontinence. International Journal of Gynecology and

Obstetrics, 138(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12232

Park, H., & Han, D. (2015). The effect of the correlation between the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles

and diaphragmatic motion during breathing. Journal of physical therapy science,

27(7), 2113–2115. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.2113

Paulus M. P. (2013). The breathing conundrum-interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety.

Depression and anxiety, 30(4), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22076

Scott, K. M., Gosai, E., Bradley, M. H., Walton, S., Hynan, L. S., Lemack, G., & Roehrborn, C. (2020).

Individualized pelvic physical therapy for the treatment of post-prostatectomy stress urinary incontinence and pelvic pain. International Urology and Nephrology, 52(4), 655–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02343-7

Stoker J. (2009). Anorectal and pelvic floor anatomy. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology,

23(4), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2009.04.008